NEP 2020: How early should children start school?

– Prof Shabana Mitra, Public Policy IIMB

The National Education Policy hopes to restructure schooling such that students begin at age 3, rather than 5 or 6 currently. Such a policy, being debated across the world, could provide especially rural parents with much-needed daycare support, and upgrade the existing Anganwadi system

The New Education Policy (NEP) has many angles being hotly debated. The introduction of regional language in schools, allowing foreign universities to open campuses in the country and many other topics have been highly contested. However, one proposal has been missing from the discourse, and could hold a silver lining.

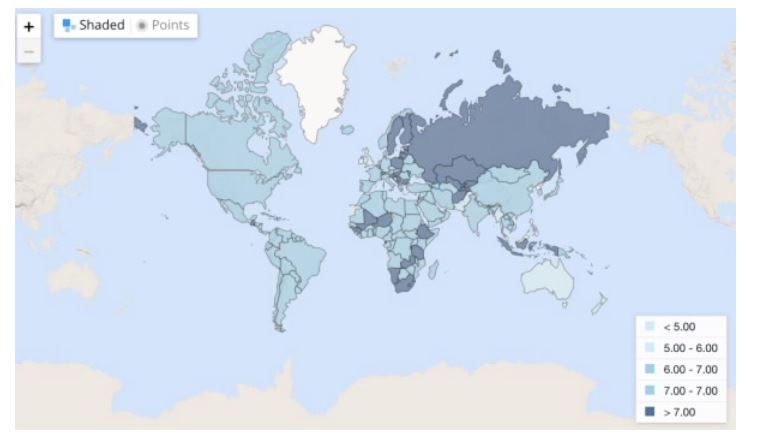

One of the proposals of the NEP is to restructure schooling into a 5+3+3+4 model. This implies starting formal or structured schooling early, at 3 years rather than the current 5-6 years in India. The average starting age for children across the world is a little over 6 years and it varies between 5 to 7 years.

What is the correct age for children to start school? Currently, this is a larger policy debate centered in the developed world. Europe, North America and the Oceania have arguments and trends going in both directions. Australia and New Zealand are debating the idea of starting formal education at the age of 4, whereas England is trying to delay it. Finland, said to have one of the best educational models in the world, starts formal schooling at age 7 for their children.

The evidence in favour of late starts suggests that children learn many lessons at home from engaging with parents and other caregivers. The cognitive development and imagination of the child is not bounded by constraints of the curriculum. David Whitebread at Cambridge University shows that constructive play builds intellectual and emotional skills that are crucial in early learning and development of the child.

On the other hand, the arguments in favour of starting school early include that children will also complete school early and so will have more earning years. Further, in a recent study, Cornelissen and Dustmann (2019) have shown that children who start early have better language and math skills, more so for children from disadvantaged family backgrounds.

In this context, what works best for a developing country? Are the challenges faced here different from those in the developed world? The difficulties faced in developed countries about formalised curriculum needs to be weighed with the developing country challenges including not having parents who have formal education, low nutritional outcomes and no access to daycare.

For India, first, we have a population where adult literacy and formal education is low, with more than 50% of the parents themselves not having gone to school. Second, thenutritional outcomes for children in India are adverse with child stunting (a long-term measure of malnourishment that shows the age appropriate height) rate of 37.9%. Finally, most of the Indian workforce is engaged in informal labour or in agriculture with no access to day care, so if the parents are working, the children are either seen sitting around in hazardous conditions in the parents workplace or the older girlchild is held back from school to take care of the younger ones. These pose hurdles to cognitive development of children as proposed by intellectuals arguing for late start.

Additionally, starting school early may be one way of increasing intergenerational mobility by ensuring all children learn at school and so the parent’s socio-economic background does not affect the outcomes of their children. Such a policy has the potential to reduce inherent inequalities based on caste and other social markers that have plagued growth in India.

On the second issue of nutrition, for most of India that still reside in rural parts of the country, the Anganwadi has been the main location where a child’s health is monitored and improved. The Anganwadi system in India was started in 1975 under the Integrated Child Development Services program to fight child hunger and malnutrition. Since then, the responsibilities of the Anganwadi have increased manifold. The Anganwadi worker has been solely responsible for monitoring pre-natal and post-natal care, tracking the immunization program and providing nutritional supplements.

For rural India, low income areas and urban slums, the Anganwadi is the only functional daycare center for parents at work or in the fields. In this current setup, the Anaganwadi then is also the place where the children are picking up their early cognitive skills.

In recent times, the Anganwadi workers have protested due to the overburdening of the system as the one stop shop for nutrition and welfare of women and children in India. The NEP initiative may further burden this overstretched system. However, if the government is serious about early start, implementation has to be seriously looked into. First, they will have to allocate a substantial budget to the Anganwadis. Second, they will have to focus on upskilling existing workers and hiring and training of many more new workers. The demand on existing infrastructure will also increase extensively. If executed efficiently, the new policy of starting school early may also result in the formalisation of the crucial institution of the Anganwadis

So there may be multiple advantages to an early start. But all this will depend on how much support is provided to the Anganwadis and how it links to other policies like universal access to education.

We can also compare this initiative with an earlier policy of the Government of India. The mid-day meal, a nutritional policy, is one of the most successful tools used by the government to increase enrolment into primary schools. Our experience tells us that nutrition and enrolment are linked in India. The NEP’s early start may be able to achieve the opposite—an enrolment program that will improve the nourishment and development of children in India.

Source: Forbes India